Disability Awareness Hub: Understanding Frontal Lobe Dementia

What is Developmental Coordination Disorder—and Why Does It Matter?

A practical guide for disability professionals

Frontal lobe dementia, more commonly referred to in clinical practice as frontotemporal dementia, is a group of neurodegenerative conditions that affect the frontal and temporal regions of the brain. These areas are responsible for personality, behaviour, decision making, emotional regulation and expressive or receptive language. When these regions deteriorate, people experience changes that can be profound and deeply confusing for families and support teams.

According to major clinical reviews, frontotemporal dementia is one of the most common causes of early onset dementia, typically affecting people between the ages of forty five and sixty five, although symptoms may appear earlier or later in life. It is progressive, meaning changes deepen as more areas of the brain are affected.

What causes frontal lobe dementia

Frontotemporal dementia occurs when nerve cells in the frontal and temporal lobes gradually die, leading to shrinkage of these regions. The underlying pathology often involves protein changes, particularly abnormalities in tau or T D P forty three proteins. Some cases are hereditary, though most are not. Approximately twenty percent of cases show a clear family history.

Recognising early signs and symptoms

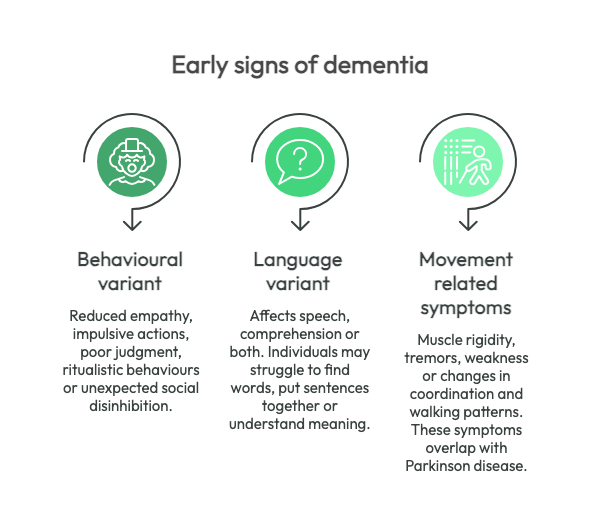

The symptoms vary depending on the specific subtype but common early features include:

Behavioural variant

People may display reduced empathy, impulsive actions, poor judgment, ritualistic behaviours or unexpected social disinhibition. These changes are often gradual and may initially be mistaken for mental health concerns, stress or relationship difficulties.

Language variant

Primary progressive aphasia affects speech, comprehension or both. Individuals may struggle to find words, put sentences together or understand meaning even though speech may remain fluent.

Movement related symptoms

A smaller percentage of people develop muscle rigidity, tremors, weakness or changes in coordination and walking patterns. These symptoms overlap with conditions such as Parkinson disease.

Because the early profile is dominated by social, emotional and behavioural changes, people are frequently misdiagnosed. Professionals who understand the nuances are better equipped to advocate for correct assessment and management.

Clinical challenges and diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on careful neurological examination, cognitive and behavioural assessment and brain imaging that can identify characteristic atrophy patterns. Some people present primarily with behavioural changes, while others show language-focused decline. The heterogeneity of symptoms means that diagnosis can be complex and often delayed.

There is no cure, but early diagnosis enables planning, targeted support and access to therapies that improve quality of life.

Evidence-informed strategies for support

Effective support is built on understanding that the person is experiencing brain based changes, not deliberate choices. Below are strategies shown to be helpful within disability and clinical practice.

1. Structure and predictability

People often respond positively to clear routines. Predictable environments can reduce anxiety and impulsive behaviours. This strategy aligns with nonpharmacologic interventions recommended in clinical management guidelines.

2. Simplified communication

Use short, concrete statements and give the individual time to respond. When expressive language is affected, communication boards or gesture-based supports can promote autonomy.

3. Redirection instead of confrontation

When behaviours become impulsive or socially challenging, redirection is more effective than correction. Supporters should gently guide the person toward an alternative activity rather than engaging in debate or attempts to reason through the behaviour.

4. Emotional and sensory regulation

Changes in emotional control are common. Calming sensory inputs such as soft lighting, familiar music or tactile objects may assist with grounding and reducing distress.

5. Collaboration with families

Families often struggle with rapid changes in personality and connection. Offering education and emotional support strengthens care networks and reduces carer stress, consistent with recommendations for caregiver involvement.

6. Strength-based engagement

Although abilities decline, many people retain interests or skills they value. Identifying preserved strengths supports dignity and purpose.

What disability professionals need to know

Frontotemporal dementia requires a distinct approach compared with other forms of dementia. Behavioural expressions are neurologically driven, not intentional. Professional teams should anticipate evolving needs and adapt plans as symptoms progress. Awareness of the condition builds capacity to respond with compassion, skill and confidence.

Current clinical literature emphasises that treatment is primarily supportive, combining behavioural strategies, tailored therapies and community resources. Professionals who understand these principles can significantly influence quality of life for both the person and their support network.

Frontal lobe dementia challenges traditional models of behaviour, communication and engagement. When we approach it with curiosity, empathy and evidence-informed practice, we create environments that honour the person and empower the people who support them.

If you're concerned about someone you know or you would like to learn more, reach out to learn how we can help.

News & Insights

Check Our Latest Resources